|

| |

|

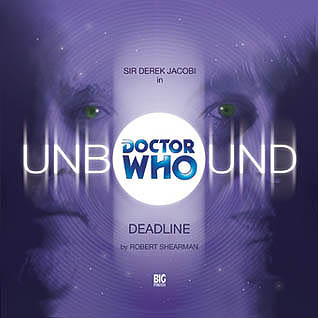

WRITTEN BY ROBERT SHEARMAN

DIRECTED BY NICHOLAS BRIGGS

RECOMMENDED PURCHASE BIG FINISH 'UNBOUND' CD #5 (ISBN 1-84435- 017-7) RELEASED IN SEPTEMBER 2003.

BLURB

It's been forty years

since Martin MET the

Doctor. They were

different men back

then. Martin was

young and talented

and The Times' 7TH

most promising NEW

writer to watch out

for. The Doctor was

possibly oriental.

It

was an encounter

that destroyed both

their lives.

Pity poor Martin now.

His career is in

ruins,

all

forgotten. His EX-

wives

keep dying in

the

wrong order, and

there's a nasty green

stain IN HIS BEDROOM

that

could be an alien

footprint,

or mould.

Martin's life is about

to change. Impromptu

poetry

readings. An

obligatory bug-eyed

monster. And a last,

desperate chance for

love, before it's too

late.

Sounds like it's time

for the Doctor to

come into Martin's

life again. And sort

him out. Permanently. |

|

|

Deadline SEPTEMBER 2003

Deadline takes the concept of Doctor Who Unbound to its logical limit, yet it is perhaps the most ordinary of all the plays in the series. Not ordinary as in mediocre; more that itís the sort of thing you wouldnít be surprised to hear on Radio 4 of an early evening. Unlike the other instalments of the series, Rob Shearmanís Deadline isnít a Doctor Who play; rather, itís a play about Doctor Who.

of Doctor Who. However, in this world, the series was never produced, and Martinís scripts languished in a drawer for decades. Instead, while his plays received critical acclaim, he was forced to write for television shows such as Juliet Bravo to make ends meet. Now, Martin lives in a care home, a loner in a world of the senile, abandoned by his family and with three failed marriages behind him. Although he regrets the failure of his personal life, itís his perceived failure as a writer that really galls him. Heís incensed that heís far better remembered for his television fluff than for his acclaimed theatre work (one wonders if Rob Shearman is channelling some of his own feeling here) Ė all the more so for the fact that he feels he sacrificed his personal life to make that happen.

Played by none other than Sir Derek Jacobi (recorded at the same time he was voicing the Master for BBCiís Scream of the Shalka webcast), Martin is a genuinely fascinating character. Although a deeply sympathetic soul, heís actually quite unlikeable much of the time - an arrogant, self-important, self-apologetic person. Yet, due to the fine writing and Jacobiís performance, which brings out the feelings of Martinís regret, the listener feels sorry for him.

The narrative centres on Martinís life as it begins to collapse. His son Philip (Peter Forbes) contacts him, distraught that heís becoming like his father. Martin has little time for him, but sees him as a way to get to his grandson (an insufferable teen oik), giving him the chance to have a family again. Barbara, a staff member at the home (played by Jacqueline King, now best known to fans as Sylvia Noble), latches onto Martin as someone she can talk to, but in the end, she is merely using him to feel better about herself. Dwelling ever more on the past, Martin begins to write again, bringing Doctor Who out of mothballs. But, as his stress rises and his life crumbles, his grip on reality lessens. He begins dreaming about Who, instead of simply writing it.

these sequences, taking on the role of the Doctor, setting it apart from his performance as Martin with a subtly different voice and a reassured, confident demeanour. As the play goes forward, Martin spends more and more time in his fantasy world with his ideal granddaughter Susan. Reality and fantasy bleed into each other, and it becomes increasingly difficult to tell which is which. The listener is drawn into Martinís confused world view.

The

eventual, catastrophic end of the play is no surprise, simply as thereís

no other direction for Martinís crisis to proceed. An exploration of guilt,

responsibility, obsession (we fans donít come out

unscathed) and even the nature of reality, Deadline is a quiet

masterpiece.

|

|

|

Copyright © Daniel Tessier 2008

Daniel Tessier has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 to be identified as the author of this work. |

|

|

Even in a range that champions the most extreme of possibilities, Deadline still manages to push the envelope. Penned by none other than Robert Shearman, Big Finish golden boy and renovator of the Daleks, this story tells of a universe where the Doctor was never real, and even the television show that he inhabits in our world never made it past the earliest stages of pre-production. In the world of Deadline, the titular Time Lord exists only as a figment of retired hack Martin Bannisterís boundless imagination, and his TARDIS is not a fantastical space / time craft, but the last refuge of a lonely scoundrel.

Deadline is unique in that it doesnít have the feel of a Big Finish audio drama. Shearman clearly had his Radio 4 hat on when he wrote the script, and this approach is mirrored in the principally spartan production. Director Nicholas Briggsí sound design is, for the most part, non-existent. The horrors of Martinís isolation are painted on silent canvas, every pity-strewn line raw. Yet when Martin thinks of the Doctor - when Martin writes - the howl of the original Ron Grainer / Delia Derbyshire theme tune opens the door to an opulent aural soundscape; every hum, every click evoking the atmosphere of Doctor Whoís earliest stories.

Martin is, in every sense, the storyís anchor. Heís present in every single scene of the play, both real and imaginary, as Shearman probes the characterís regrets and failings with his usual deathly poise. Once a promising playwright, Martin soon found himself contracted to the BBC, churning out hackneyed scripts for Juliet Bravo that still set internet forums ablaze, whilst his acclaimed flop díťstimes have faded into obscurity. This perceived failure has left Martin embittered, particularly as his fanatical passion for his work sullied every relationship that he ever tried to form. The play thus deals with both aspects of Martinís life, Shearman gently poking fun at us Doctor Who obsessives (whilst betraying his own arcane knowledge of the show!) as Martin retreats further and further inside his own mind, eventually taking on the mantle of the character he created: ďDr WhoĒ.

Quiet fittingly for an anniversary release, the script is abounding with playful nods and winks that have been woven right into the storyís core. Series creator Sydney Newman is used to demonstrate Martinís utter lack of interest in other people, the ghost of his former producerís accent oscillating between Australian and Canadian because Martin canít quite remember where he was from. This point is then made explicit as the modulated voice of the Supreme One, the principal antagonist in Anthony Coburnís aborted Masters of Luxor, launches an attack on Martinís inability to understand real people, and the trite characterisation that flows from the same.

Deadlineís author, however. Just like the characters that populate his award- winning short stories, the inhabitants of this script are almost too real; too grey and textured. A hate-filled son isnít just a hate-filled son, but a tormented soul whose life has fallen apart, driving him to cremate guinea pigs just to give him an excuse to speak to his estranged Dad. A lonely nurse isnít just a lonely nurse, but an aspirant poet and jilted bride, her science teacher fiancť having long-since vanished from the face of the Earth. A bitter old washed-up writer isnít just a bitter old washed-up writer, but a sympathetic soul; a troubled, and potentially dangerous, old man crushed by the weight of unfulfilled potential, whose ex-wives wonít even die in the proper order.

Happily, the ensemble cast are equal to the script. Sir Derek Jacobi, the only man to play both the Doctor and the Master (unless you count Mark Gatissí humorous turn as the Time Lord in the BBCís Doctor Who Night skits), vests the total sum of his gravitas in poor old Martin, squeezing every last ounce of regret and spite out of each word put in front of him. His co-stars are every bit as extraordinary, particularly as they are required to flit effortlessly between realities, playing not only their respective characters but their fictional reflections too. Peter Forbes (Philip) and new series star Jacqueline King (Barbara) both stand out in particular, each giving two completely contrasting performances. Their agents should have charged double.

For me, Deadline is not only the finest Unbound adventure of

the lot, but one of the most stunning plays that Big Finish have produced

to date. Any Doctor Who story sporting the lines ďDr Who, you

bastard!Ē (wrong in so, so many ways) and ďwe both have full bladder

controlĒ should crash and burn by all rights, but under Shearmanís

stewardship it simply soars. If youíre only going to listen to one

Unbound story, do yourself a favour and make it this one.

|

|

|

Copyright © E.G. Wolverson 2010

E.G. Wolverson has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 to be identified as the author of this work. |

|

|

Unless otherwise stated, all images on this site are copyrighted to the BBC and are used solely for promotional purposes. ĎDoctor Whoí is copyright © by the BBC. No copyright infringement is intended. |

|

.jpg)

The story involves Martin

Bannister, fictional creator

The story involves Martin

Bannister, fictional creator

This

criticism could not be levelled at

This

criticism could not be levelled at